Self-Employment Tax: Partners

Photography and writing by Musa Jemal

“But we’re against those entrusted with this program when they practice deception regarding its fiscal shortcomings, when they charge that any criticism of the program means that we want to end payments to those people who depend on them for a livelihood. They’ve called it “insurance” to us in a hundred million pieces of literature. But then they appeared before the Supreme Court and they testified it was a welfare program. They only use the term “insurance” to sell it to the people. And they said Social Security dues are a tax for the general use of the government, and the government has used that tax. There is no fund, because Robert Byers, the actuarial head, appeared before a congressional committee and admitted that Social Security as of this moment is 298 billion dollars in the hole. But he said there should be no cause for worry because as long as they have the power to tax, they could always take away from the people whatever they needed to bail them out of trouble. And they’re doing just that.”

-Ronald Reagan, “A Time for Choosing”

“To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy – a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.”

-Frederick Douglass, “Fourth of July Speech”

Background

To address the needs of millions of Americans that were unemployed during the Great Depression, FDR tasked Frances Perkins, the first female cabinet member, to develop an old-age insurance program. In 1935, the resulting Social Security Act was signed into law as a program to provide financial security for individuals and their families through old-age pensions, disability and survivor benefits and insurance tax (“social security tax”). To fund the Social Security program, tax is imposed on “wages” by Federal Insurance Contributions Act of 1935 (“FICA”). Wages are defined in the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) § 3121(a) as including “all remuneration for employment” with certain specific exceptions. Generally, the “employment tax” (aka FICA tax), is imposed on both employers and employees with the employees’ portion of the tax being collected by the employer through withholding. FICA also includes the Hospital Insurance tax (“Medicare tax”). The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (“FUTA”) taxation provisions are similar to the FICA provisions, except that only the employer pays the tax imposed under FUTA.

In determining whether a worker is an employee, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) has developed various common law facts or factors that it considers. For example, Rev. Rul. 87-41, 1987-1 CB 296, provides a list of 20 factors that may be examined in determining whether an employer-employee relationship exists. The factors of Rev. Rul. 87-41 are as follows:

Instructions. Whether a worker is required to comply with service recipient’s instructions about when, where, and how he or she is to work.

Training. Whether a worker requires training so that services are performed in a particular method or manner.

Integration. Whether the success or continuation of a business depends to an appreciable degree upon the performance of certain services of the worker, that are integrated into the business operations.

Services Rendered Personally. Whether services must be rendered personally.

Hiring, Supervising, and Paying Assistants. Whether service recipient hires, supervises, and pays assistants.

Continuing Relationship. Whether there is a continuing relationship between the worker and service recipient.

Set Hours of Work. Whether there is an establishment of set hours of work by service recipient.

Full Time Required. Whether the worker must devote substantially full time to the business of the service recipient.

Doing Work on Employer’s Premises. Whether the work is performed on the premises of the service recipient.

Order or Sequence Set. Whether a worker must perform services in the order or sequence set by service recipient.

Oral or Written Reports. Whether there is a requirement that the worker submit regular or written reports to the service recipient.

Payment by Hour, Week, Month. Whether payments are by the hour, week, or month

Payment of Business and/or Traveling Expenses. Whether the service recipient ordinarily pays the worker’s business and/or traveling expenses.

Furnishing of Tools and Materials. Whether the service recipient furnishes significant tools, materials, and other equipment.

Significant Investment. Whether the worker invests in facilities that are used by the worker in performing services and are not typically maintained by employees.

Realization of Profit or Loss. Whether a worker can realize a profit or suffer a loss as a result of the worker’s services (in addition to the profit or loss ordinarily realized by employees)(e.g., the worker is subject to a real risk of economic loss due to significant investments or a bona fide liability for expenses).

Working for More Than One Firm at a Time. Whether a worker performs more than de minimis services for a multiple of unrelated persons or firms at the same time.

Making Service Available to General Public. Whether a worker makes his or her services available to the general public on a regular and consistent basis.

Right to Discharge. Whether the service recipient possess the right to discharge a worker.

Right to Terminate. Whether the worker has the right to end his or her relationship with the service recipient at any time he or she wishes without incurring liability.

The significance of each factor in Rev. Rul. 87-41 varies by occupation and factual context in which the services are performed, with unlisted factors potentially being relevant. Some of these factors were applied by the IRS in P.L.R. 9345037 to determine whether a worker was an employee of the tribal casino for purposes of FICA, FUTA, and Federal income tax withholding. In that case, the stipulated facts were as follows:

The service recipient was an Indian tribal organization that operated a bingo/gambling operation and the worker was engaged in making bingo cards;

The worker performed services at the service recipient’s location and earned hourly wages;

Either the service recipient or the worker could terminate the agreement for services at any time without incurring liability;

The worker had a continuous relationship with the service recipient as opposed to a single transaction;

The worker reported daily and worked approximately eight hours per day;

The service recipient had the right to change the methods used by the worker and to direct the worker in how the work was to be done;

The service recipient furnished the worker with all the necessary tools and materials needed to make the bingo cards.

Under those facts, the IRS concluded that: (i) the worker was an employee of the Indian tribal organization for purposes of the FICA, the FUTA, and Federal income tax withholding; (ii) that the federal employment taxes, including income tax withholding, applied with regard to all wages paid in employment, unless there was a specific exception; and (iii) that there was no exception for services performed for an Indian tribe. Therefore, for both FICA and FUTA taxes, as well as income tax withholding, Indian tribes, notwithstanding their sovereignty, were treated in the same way as private employers.

However, partners are not considered employees in a partnership. See Rev. Rul. 69-184; 1969-1 C.B. 256 (which explicitly provides that bona fide members of a partnership are not employees of the partnership within the meaning of FICA and/or FUTA but are “self-employed” individuals. Rev. Rul. 69-184 applies the usual common law rules to provide that a partner who devotes his time and energies in the conduct of the trade or business of the partnership, or in providing services to the partnership, as an independent contractor, is in either case a self-employed individual rather than an individual who has the status of an employee); see also CCA 201916004 (2019). The term “self-employed” also includes sole proprietors and independent contractors. A bona fide partner does not receive remuneration for services from a partnership as wages with respect to employment but a distributive share of items of partnership income, loss, deduction, or credit. The significant implication of classifying a partner as a non-employee is that both the partner providing the service and the partnership receiving the service are not subject to the taxes imposed by FICA and/or FUTA. However, partners, sole proprietors and independent contractors are brought into the Social Security program through the Self-Employment Contributions Act of 1954 (“SECA”).

General rule of SECA

SECA imposes a tax on an individual’s “self-employment income.” See IRC §§ 1401(a) and 1401(b), respectively, which impose for each taxable year, Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance tax and Medicare tax on the self- employment income of every individual. Self-employment income is a key term, defined in IRC § 1402(b), to mean the individual’s “net earnings from self-employment.” In turn, IRC § 1402(a) defines “net earnings from self-employment” (“NESE”) generally as:

The gross income derived by an individual from any trade or business carried on by such individual, less

The deductions allowed which are attributable to such trade or business, plus

The individual’s distributive share (whether or not distributed) of income or loss described in IRC § 702(a)(8) from any trade or business carried on by a partnership of which he is a member.

Specifically, IRC § 702(a)(8) requires partners to separately account for the partnership’s taxable income or loss, exclusive of items requiring separate computation. This statutory category generally represents the partnership’s ordinary business income from operations. Therefore, a partner’s distributive share of this IRC § 702(a)(8) income is included in NESE and thus generally subject to SECA tax, unless an exception applies. Absent an exception, self-employment income includes all gross income derived by an individual from any trade or business carried on by the individual as other than an employee. For example, where an individual is a sole owner and operator of a sole proprietorship that performs services as a mason and concrete laborer, their net earnings derived from their masonry and concrete business are characterized as self-employment income. See Porter v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2015-122. Likewise, if the masonry and concrete services are performed by an independent contractor who is paid in virtual currency, the fair market value of the virtual currency measured in U.S. dollars as of the time of receipt would constitute self-employment income and be subject to the self-employment tax, with this same value establishing the recipient’s basis in the virtual currency. See also James Clark v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2025-13 (held that income received from freelance movie review writing and selling movie-related memorabilia on eBay was subject to self-employment tax); Rev. Rul. 55-385; 1955-1 C.B. 100 (held that a university professor’s royalties and other income received from the professor’s side hustles of writing books and giving lectures, was subject to self-employment tax); Slaughter v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2019-65, affirmed by Slaughter v. Commissioner, No. 20-10786 (11th Cir. 2021) (an author’s income from publishing contracts derived from her trade or business was subject to self-employment tax).

Statutory Construction: Limited Partner Exception

Under IRC § 1402(a)(1)-(17), there are several exclusions from NESE. Specifically, IRC § 1402(a)(13) excludes the distributive share of any item of income or loss of a limited partner, as such, other than guaranteed payments described in IRC § 707(c) to that partner for services actually rendered to or on behalf of the partnership to the extent that those payments are established to be in the nature of remuneration for those services (the “LP Exception”). The phrase “as such” is an adjectival modifier of “a limited partner.” Adjectival modifiers restrict the scope of the noun they modify. “As such” limits the exclusion only to distributive shares earned by a partner in the capacity of a limited partner, creating ambiguity as to whether: (i) it strictly refers back to the antecedent to clarify that the exclusion applies to state law limited partner as formally classified as such limited partner; or (ii) it modifies the antecedent to imply a federal income tax-specific meaning that the exclusion applies only if the partner’s distributive share arises strictly from the limited partner’s role as a passive investor, not from active participation in the partnership’s business. Said another way, “as such” is ambiguous as to whether a partner should be considered a limited partner solely because their liabilities are limited under state law (“state-law status”), or whether federal tax law should look beyond state law classification when the partner’s substantive activities functionally resemble those of an active, non-passive investor (“functional role”).

If we delete “as such,” than the exclusion may apply to all distributive share of any item of income or loss of a limited partner, other than guaranteed payments and even then, only to the extent that those payments are established to be in the nature of remuneration for those services. Then the question becomes why Congress would exclude from NESE all other remuneration for services of a limited partner but single-out guaranteed payments for taxation, and why only to the extent that they are in the nature of remuneration for those services? If we keep “as such” and interpret the intent of Congress to mean that “as such” means limited partner functioning as a limited partner, then, the singling-out of guaranteed payments becomes superfluous because guaranteed payments in the nature of remuneration for services are inherently non-“as such” activities? Perhaps it’s not superfluous if we infer that Congress explicitly referenced guaranteed payments to address a special type of payment that are derived in part from as such” activities (i.e., returns in the nature of investment) and in part from non-“as such” activities (i.e., remuneration for services).

Generally, a partner who renders services to a partnership other than in his capacity as a partner is treated as if he were not a member of the partnership with respect to such services. See Treas. Reg. § 1.707-1(a). Guaranteed payments are regarded as a partner’s distributive share of ordinary income but are considered as made to one who is not a member of the partnership for purposes of IRC §§ 61(a) (relating to gross income) and 162(a) (relating to trade or business expenses). Guaranteed payments are payments made by a partnership to a partner for services or for the use of capital, and to the extent such payments are determined without regard to the income of the partnership, they are considered as made to a person who is not a partner. However, a partner must include such payments as ordinary income for his taxable year within or with which ends the partnership taxable year in which the partnership deducted such payments as paid or accrued under its method of accounting. See Treas. Reg. § 1.707-1(c). See also Pratt v. Commissioner, 64 T.C. 203 (1975), aff'd in part, rev'd in part, 550 F.2d 1023 (5th Cir. 1977) (held that management fees computed as a percentage of gross rental income received by the limited partnership formed to purchase, develop, and operate a shopping center were not guaranteed payments to the general partners who contributed managerial services. The Court’s reasoning was that the payments were not “determined without regard to the income of the partnership” as required by the statute to come within the meaning of guaranteed payments); Rev. Rul. 81–300 (1981–2 C.B. 143), obsoleted (held under similar facts in Pratt that the management fees were guaranteed payments under IRC § 707(c) because they were compensation for managerial services payable without regard to partnership income).

Now, it would be nice to have a congressional made definition of what a limited partner the phrase “as such” was referring to, but unfortunately, the definition of a “limited partner” does not exist in the applicable statute. The legislative history provides that this language was meant to “exclude from social security coverage, the distributive share of income or loss received by a limited partner from the trade or business of a limited partnership. This is to exclude for coverage purposes certain earnings which are basically of an investment nature.” See H. Rept. 95-702 (Part 1), at 11 (1977). Dating back to 1977, it has been permissible under Delaware law for the same partner to wear two hats, a limited partner hat and a general partner hat. See Del. Code. Ann. tit. 6, §1712 (1977). Is “as such” getting at this permissible duality and allowing LP Exception from NESE only when the general partner puts on his LP hat, or is “as such” imposing a functional test to determine whether activities of the limited partners are, in their nature, investments? For example, does it matter how many hours a state law limited partner participates in the partnership’s trade or business? The proposed regulations promulgated in 1997 by the Treasury Department and the IRS defined “limited partner” for IRC § 1402(a)(13) purposes and provided that an individual is treated as a limited partner unless the individual, among other things, participates in the partnership’s trade or business for more than 500 hours. However, the proposed regulations expired and were never finalized after Congress, in its great wisdom and clairvoyance, imposed a temporary moratorium on finalizing the 1997 proposed regulations.

Today, the IRS argues that the interpretation of IRC §1402(a)(13) is not controlled by state partnership law for the following reasons. The Constitution grants Congress plenary taxing authority and establishes federal supremacy over state law. See U.S. Const. art. I, §8, cl. 1 (taxing power) and art. VI, cl. 2 (supremacy clause). Federal tax statutes derive from this exclusive constitutional power. Lyeth v. Hoey, 305 U.S. 188, 194 (1938). Federal law governs federal tax statutes; state law is subordinate unless the federal statute by express language or necessary implication depends on state law. See Burnet v. Harmel, 287 U.S. 103, 110 (1932)(holding that the federal tax consequences of the characterization of oil-and-gas lease was not controlled by state law). Thus, statutory interpretation of federal tax statutes is inherently a federal question and therefore, “not determined by local law.” Lyeth, 305 U.S. at 193.

State-law labels do not control federal tax consequences “no matter what name is given to the interest or right by state law.” Morgan v. Commissioner, 309 U.S. 78, 80-81 (1940); Air Power, Inc. v. United States, 741 F.2d 53, 56 (4th Cir. 1984) (held federal definition of state court as “court of record” overrides state label classifying it as a “court not of record”); Maines v. Commissioner, 144 T.C. 123, 132 (2015) (“a particular label given to a legal relationship or transaction under state law is not necessarily controlling for federal tax purposes”). Thus, it is the federal law that defines statutory terms irrespective of state classifications. Morgan, 309 U.S. at 80 (held that a particular power of appointment was “general within the intent of the Revenue Act, notwithstanding [that it] may be classified as special by the law of Wisconsin”; Heiner v. Mellon, 304 U.S. 271, 279 (1938)(held that liquidating trustees under Pennsylvania law were partners for purposes of the federal income tax, and therefore, were taxable on their proportionate shares of the partnership earnings, even though its distributing was prohibited under state law until the satisfaction of all of the partnership’s liabilities and debt.)

Federal law controls entity classification for tax purposes. See, e.g., IRC § 7701 (defining terms including, partnership, and partner); Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-1(a) (“[w]hether an organization is an entity separate from its owners for federal tax purposes is a matter of federal tax law and does not depend on whether the organization is recognized as an entity under local law”); Burke-Waggoner Oil Ass’n v. Hopkins, 269 U.S. 110, 111-14 (1925)(held that an unincorporated joint-stock association was taxed as corporation for federal tax purposes and rejected the application of a conflicting state law that deemed the association as a partnership); Moore v. United States, 144 S. Ct. 1680, 1689 (2024) (quoting Burke-Waggoner, 269 U.S. at 114)(“[n]either the conception of unincorporated associations prevailing under the local law, nor the relation under that law of the association to its shareholders, nor their relation to each other and to outsiders, is of legal significance as bearing upon the power of Congress to determine how and at what rate the income of the joint enterprise shall be taxed”); Commissioner v. Culbertson, 337 U.S. 733, 742 (1949) (held that whether there was a true partnership required the consideration of all the facts, including, “the agreement, the conduct of the parties in execution of its provisions, their statements, the testimony of disinterested persons, the relationship of the parties, their respective abilities and capital contributions, the actual control of income and the purposes for which it is used, and any other facts throwing light on their true intent.” A bona-fide partnership, therefore, exists for federal income tax purposes when the facts show that “the parties in good faith and acting with a business purpose intended to join together in the present conduct of the enterprise”); Second Carey Tr. v. Helvering, 126 F.2d 526, 528-29 (D.C. Cir. 1942) (held that for federal tax purposes, an association was taxable as a corporation, even though the association was an “express trust” under Oklahoma law. Thus, entity status is determined by federal law, not state labels.

An individual’s tax status vis-à-vis an entity is a federal question. Heiner, 304 U.S. at 279 ( held that state law liquidating trustees were partners for federal tax purposes). State-law labels of individual roles (e.g., “partner,” “trustee”) are not conclusive. Heiner, 304 U.S. at 279; see also PPL Corp. v. Commissioner, 569 U.S. 329, 335 (2013)(reaffirming Heiner’s holding that “state-law definitions [are] generally not controlling in federal tax context”).

The general rule, therefore, is that IRC § 1402(a)(13) is a federal tax statute, and its interpretation is not controlled by state law unless the federal statute by express language or necessary implication depends on state law. Here, the argument against the IRS’ position is that IRC § 1402(a)(13) does fall within the exception and therefore, does depend on state law and is not divergent from it. Federal law does not define the term “limited partner” and by not defining the term at the time of enactment or thereafter, Congress must have intended to rely not on the “label” but on the “ordinary meaning” of the term “limited partner” under state law. The phrase, “limited partner, as such” in IRC § 1402(a)(13) must therefore by necessary implication depend on state law.

The opposing argument to the IRS provides that the interpretation of federal tax statutes (including IRC § 1402(a)(13)) is governed by federal law, but that, in this case, state law controls because the federal statute by necessary implication depends on state law (Burnet v. Harmel, 287 U.S. 110 (1932); Heiner v. Mellon, 304 U.S. 279 (1938)). Here, federal law does not define “limited partner” in IRC § 1402(a)(13); this fact distinguishes this case from cited cases where there was a divergence between federal law definition and state law definition. Here, there is no such conflict because only state law defines limited partner. When Congress leaves a term undefined, it adopts the term’s ordinary meaning at the time of enactment. See FDIC v. Meyer, 510 U.S. 471, 476 (1994). The ordinary meaning of “limited partner” at the time of enactment derived from state law (uniform adoption of ULPA/RULPA). Congress necessarily relied on state law’s ordinary meaning of “limited partner,” not state-law labels. The phrase “limited partner, as such” in IRC § 1402(a)(13) incorporates the state-law ordinary meaning of “limited partner”. A federal statute depends on state law by necessary implication when it adopts state-law definitions to give meaning to undefined terms. See Boggs v. Boggs, 520 U.S. 833, 845 (1997). Therefore, IRC § 1402(a)(13) by necessary implication depends on state law for the meaning of “limited partner, as such” (triggering Burnet’s exception).

Law & Analysis

In 1991 the Texas legislature passed the first Limited Liability Partnership (“LLP”) legislation. Two decades later, the IRS brought its first LLP case against Renkemeyer, Campbell & Weaver, LLP, a law firm engaged in the practice of law as a Kansas limited liability partnership. The IRS put forward a functional analysis theory to impose self-employment taxes on the law firm’s practicing lawyers. In Renkemeyer, Campbell & Weaver, LLP v. Commissioner, 136 T.C. 137 (2011), the Tax Court employed the functional analysis test to examine the substance of the partners’ distributive shares to determine whether the law firm’s revenues were derived from legal services performed by the lawyers or were instead returns on the partners’ investment. The Tax Court found that substantially all the revenue of the law firm were derived from legal services performed by petitioners in their capacities as partners and held that the lawyers were not limited partners within the meaning of IRC § 1402(a)(13). The rationale of the Tax Court was that the partners contributed nominal capital and actively participated in the partnership’s business operations. Thus, the partners were subject to self-employment taxes, notwithstanding the partners’ designation as limited partners under state corporate law.

Prior to Renkemeyer, the IRS was able to secure victories and impose self-employment tax on earnings of individuals who owned working interests in oil and gas joint ventures, notwithstanding the individual’s lack of participation in the business operations. See Cokes v. Commissioner, 91 T.C. 222 (1988) and Perry v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 1994- 215. But it was not until Renkemeyer, that the IRS was successfully able to impose self-employment tax on state law entities such as LLPs registered under the corporate laws of a state and observant of the formalities of state law. Bolstered by its victory in Renkemeyer, the IRS has expanded audits and litigations against many other pass-through state law entities (i.e., limited liability company (“LLC”), limited partnership (“LP”) and limited liability limited partnership (“LLLP”)) to impose self-employment tax on limited partners that actively participate in the partnership’s business operations. For example, on May 20, 2014, the IRS imposed self-employment tax on the distributive shares of partners in an LLC, where the LLC’s primary source of income was from fees for providing investment management services. See CCA 201436049 (Similar to Renkemeyer in that the earnings of the partners were attributable to fees generated from the direct result of the services rendered by the partners on behalf of the LCC. However, distinguishable from Renkemeyer in that the contributions of the partners were more than a nominal amount). See also Treas. Regs. § 1.415-2(d)(2)(i), which includes fees for professional services as an item within the definition of compensation.

For a string of other IRS victories in applying the functional analysis test to determine how the partners generated income from LLC partnerships see, e.g.,; Howell v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012-303 (finding that payments to an LLC member were for services rendered to the LLC. In that case, services consisted of, among other things, exercising management authority, providing marketing advice, signing documents and entering into contracts on behalf of the LLC, contributing a business plan and intellectual property to the LLC); Hardy v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2017-16 (finding that a surgeon who held a minority interest in an LLC that operated a surgery center was a limited partner for purposes of IRC § 1402(a)(13)); and Castigliola v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2017-62 (finding professional LLC members were not limited partners for purposes of IRC § 1402(a)(13)).

Building on its arguments in CCA 201436049, the IRS went after Soroban Capital Partners LP, a hedge fund manager with multi-billion-dollars assets under management (“AUM”) that concentrates its investment on public companies and utilizes an investment strategy of long/short and long only equity. In Soroban Capital Partners LP v. Commissioner, 161 T.C. 310 (2023) (“Soroban I”), the Tax Court held for the first time that it had jurisdiction to determine a state law limited partner’s status for the purpose of applying the LP Exception to state law limited partnerships. Because NESE is required to be calculated at the partnership level, argued the Tax Court, any adjustment to this calculation had to be made in a partnership-level proceeding. The Tax Court has jurisdiction in partnership-level proceedings over determinations of partnership items; here, determining whether Soroban’s limited partners’ ordinary business income shares were excluded from NESE (a partnership item required under Subtitle A) was such a case—therefore, jurisdiction existed. The Tax Court held, further, that limited partners in a LP must satisfy a functional analysis test to benefit from the LP Exception. However, the Tax Court did not apply the factual inquiry until Soroban Capital Partners LP v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2025-52 (“Soroban II”). Between Soroban I and II, the IRS returned to the Tax Court with a case against Sirius Solutions, L.L.L.P, an independent business consulting firm specializing in the areas of financial advisory, business operations, compliance and controls, legal and economic advisory and technology. In Sirius Solutions, L.L.L.P. v. Commissioner, No. 30118-21 (T.C. Feb. 20, 2024) (stipulated decision), the Tax Court made adjustments to the partnership items of Sirius Solutions, L.L.L.P., in light of Soroban I, allowing Sirius Solutions to appeal with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. In that same year, another case in the Tax Court was decided against Denham Capital Management LP, a private equity and credit fund with a multi-billion dollars in AUM that concentrates its investment on sustainable infrastructure assets, critical metals and minerals and provides credit solutions to companies contributing to the energy transition worldwide. In Denham Capital Management LP v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2024-114, the Tax court adhered to horizontal stare decisis in affording precedential weight to Soroban I. The Tax Court affirmed that the determination of the applicability of the LP Exception is a partnership item over which the Court had jurisdiction and that such determinations under IRC § 1402(a)(13) required a functional analysis test to determine how the partnership generated the income in question and the partners’ roles and responsibilities in doing so.

The Tax Court in Denham followed the reasoning in Renkemeyer and found that “Denham’s income [approximately $130 million in revenue] for 2016 and 2017 consisted solely of fees it received in exchange for services provided to investors such as advising and operating the private investment funds.” See Denham, T.C. Memo. 2024-114 at 15.

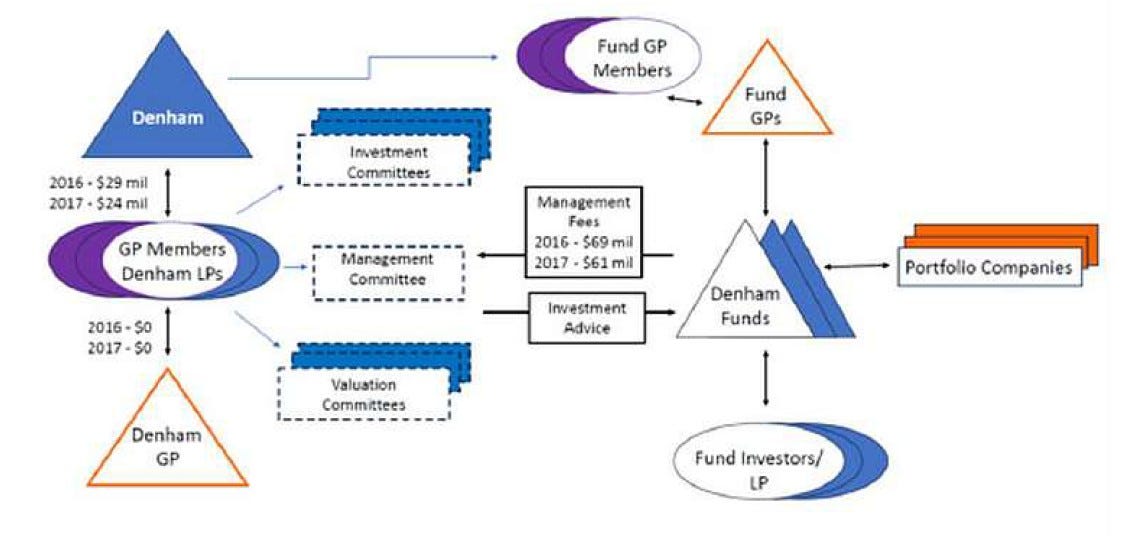

Structure chart from IRS’ court filing

The Tax Court reasoned that the amounts at issue were not partners’ distributive shares arising out of returns on investments for the following reasons: (i) there was an absence of capital contributions by the limited partners and a single partner’s initial investment were too small relative to the substantial fees received by that partner; (ii) the partners were employed full-time, “devote[d] substantially all of their time to Denham,” and served on the management, investment and valuation committees or exercised delegated authority; (iii) the Fund’s Private Placement Memorandums (“PPM”) solicited capital commitments by marketing the partners’ expertise and judgment and the partners ability to make investment decisions through the investment committee; (iv) the active role of the partners were further evidenced by the partners’ power to admit new partner, to hire/fire employees and make decisions on compensation packages, either through the management committee or through unilateral action; (v) it could be inferred that the guaranteed payments were below market-level salary due to the excess payments which evidenced “a substantial and active business operation, which included the [p]artners”; (vi) and although Denham “contends that the funds were independent and could refuse the recommendations of the [p]artners,” there was no evidence that any “[p]artners’ investment recommendations were refused in practice.” See Denham, T.C. Memo. 2024-114 at 15-17. Denham has filed an appeal with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit.

In Soroban II, the Tax Court carried out a factual inquiry to determine whether the limited partners of Soroban were functionally acting as limited partners. The Tax Court determined that Soroban’s limited partners were not acting as limited partners for the following reasons: (i) they contributed little to no capital relative to their shares of income; (ii) their unique skills and experience were indispensable to the business; (iii) they exercised managerial control over Soroban and worked full time with Soroban; (iv) Soroban’s income derived from investment management; and (v) they played an essential role in generating this income.

Soroban had a typical fund structure with Soroban Capital Partners GP, LLC (“general partner”) and three individual state-law limited partners (EWM1 LLC, GKK LLC, and Scott Friedman). The single member entities, EWM1 LLC and GKK LLC, were wholly owned by Eric Mandelblatt and Guarav Kapadia, respectively and were treated as disregarded entities because there was no election in place to treat the entities as separate from their owners.

Soroban managed a total of 11 funds which were grouped into a master-intermediate-feeder (Master Fund and the Opportunities Fund) and a master-feeder (Special Fund) structure. Soroban’s management fees from the funds, which could be waived at Soroban’s discretion, ranged from 0 to 1.5% and were charged at the master fund level. For the years at issue (2016 and 2017), Soroban was paid by the Master Fund and the Opportunities Fund an amount of approximately $247 million in fees. The amounts of the payments to Soroban were characterized “as expenses for management services” by the Master Fund and the Opportunities Fund “on their ‘Statement of Operations’ for 2016.” See Soroban II, T.C. Memo. 2025-52 at 7. To determine whether the amounts of the payments from the Master Fund and the Opportunities Fund to Soroban were excludable from “a partner’s distributive share of partnership income from [NESE]” as distributive shares of income of an investment nature, a functional analysis was required. See Soroban II, T.C. Memo. 2025-52 at 16, citing to Renkemeyer and Denham.

For purposes of applying the functional analysis test, the IRS proposed a list of nine factors:

“whether the limited partner was treated as a limited partner under applicable state law;

whether the limited partner engaged in any conduct that would result in the limited partner’s losing his status as a limited partner under state law;

whether the limited partner also held an interest in the partnership as a general partner;

whether the limited partner had a capital investment in the partnership;

whether the limited partner received separate compensation for any services provided to the partnership;

whether the earnings of the partnership were solely attributable to services provided by the limited partners;

whether the amount of earnings allocated to each limited partner was determined by reference to the services provided by that limited partner to the partnership;

whether the terms of the limited partnership agreement authorized the limited partners, in their capacity as limited partners, to exercise managerial authority or bind the partnership in contracts and in other ways; and

whether any persons, other than the limited partners, exercised managerial authority, or held the authority to bind the partnership in contracts and in other ways.” See Soroban II, T.C. Memo. 2025-52 at 19.

The Tax Court was not persuaded by “any set number of factors” in determining “whether a partner functions as a general partner or a limited partner for federal tax purposes” and opted for an expansive “facts and circumstances test that takes into account all relevant facts and circumstances.” Ibid. Additionally, the Tax Court stressed that state law “[l]abels are perhaps least relevant because they may be inconsistent with the economic reality of a partner’s relationship with the entity.” Ibid, at 20. The Tax Court’s functional analysis test in Soroban II applied five factors:

The Principals’ role in generating income;

a. Here, Principals worked full-time for Soroban (approximately 2,300-2,500 hours/year), with 100% of their effort dedicated to its management and investment activities.

The Principals’ role in management;

a. Here, all three Principals actively managed Soroban through key committees (e.g., hiring/firing decisions) and had authority to execute business agreements. While other employees existed, the Principals controlled core operations.

The Principals’ time devoted to the business;

a. Here, the Principals worked full-time for Soroban (approximately 2,300-2,500 hours/year), with 100% of their effort dedicated to its management and investment activities.

Marketing the Principals’ role in the business; and

a. Here, Soroban marketed the Principals’ expertise to investors as essential. Mandelblatt’s incapacity would trigger investor withdrawal rights, and fund liquidation would occur if no Principal was available.

The Principals’ capital contributions.

a. Here, Kapadia/Friedman contributed $0 capital. Mandelblatt contributed $4M but received $80M in distributions—grossly disproportionate to his investment and Soroban’s $247M income. Distributive shares were not returns on capital investment. Ibid, at 17 to 19.

Soroban II held that state law “limited partners” label placed on Soroban’s Principals are not controlling where the Principals’ functional roles were one of active engagement in running the business. They were crucial for generating income, handled day-to-day management, worked full-time, and were held out to the public as key personnel. Their earnings, as shown in their capital accounts, stemmed from active participation, not investment. In conclusion, they fail to meet IRC § 1402(a)(13)’s definition of limited partners, and their earnings constitute NESE during the years at issue, substantially increasing their tax liability.

Partnership tax distributions to cover NESE tax liability

Generally, funds are made up of passive investors that include high-net-worth individuals, tax-exempt entities (e.g., universities), state pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds. If the general partner has negotiated for tax distribution out of the partnership to cover NESE tax liability, including with respect to management fees, these passive investors may have to come out of pocket to cover these tax liabilities. Often, Limited Partnership Agreements (“LPA”) anticipate NESE tax liability and provide for tax distributions to cover the tax liability on account of the carried interest. The rationale is that tax distributions might be necessary to fix the mismatch where a partner’s tax liability arising out of the partnership’s activities is more than the cash distributions made by the partnership to that partner.

Tax distributions may be necessary in cases where the partnership throws off “phantom income” either because: (i) there is a tax liability against the partners without a corresponding cash (e.g., cash proceeds from a sale of an asset) for the partners to be able to pay the tax liability; or (ii) the general partner has a back-end-loaded carry (also known as “European style” carry), where the distributions to the general partner are not allowed until the passive investors receive return of capital and preferred return. The “American-style” carry mitigates this phantom income issue because the distributions waterfall is investment-by-investment, as opposed to the European style aggregate fund level approach. Thus, as investments are realized, the general partner receives distributions of cash with which it satisfies its tax liability, as long as the realized investment is above the preferred return. Most LPA’s tax distributions are made for items of the partnership that are attributable to carried interest, not management fees. However, LPAs are negotiated contracts and it may be that passive investors have agreed to cover NESE liabilities not only on account of carried interest but also on account of management fees.

In Atalaya Capital Management LP v. Commissioner, Docket No. 03253-25, a case presently pending before the Tax Court, the IRS increased Atalay’s NESE for the tax years ending December 31, 2016 and December 31, 2017, by $8,907,732 and $10,007,198, respectively. If the IRS prevails, the limited partners will be subject to tax liability on the above adjustments. Query whether Atalay’s LPA included a tax distribution and whether self-employment tax liability was included in the income subject to the tax distribution. To complicate the matter, Atalaya was acquired in 2024 by Blue Owl Capital Inc, a Delaware corporation with over $62 billion in AUM. The acquisition of Atalaya was a strategic expansion by Blue Owl to protect its position as the leading alternative asset management firm providing private credit to middle- and upper middle-market businesses. The 2025 LPA of Blue Owl Capital Holdings LP provides a tax distribution provision that takes into account self-employment taxes. The relevant definitions and provisions with respect to Blue Owl Capital Holdings LP’s tax distributions is based on the reasonable estimates of the General Partner and assumes the highest combined maximum marginal tax rate, and takes into account, seemingly without distinguishing between carry and management fees, the self-employment taxes of IRC § 1401. See the relevant provisions below:

Definitions

“Assumed Tax Liability” means, with respect to a Partner for a taxable period to which an applicable Tax Distribution under Section 4.2 relates, an amount equal to the United States federal, state and local income taxes (including applicable estimated taxes) that the General Partner reasonably estimates would be payable by such Partner with respect to such taxable period, (i) assuming such Partner earned solely the items of income, gain, deduction, loss, and/or credit allocated to such Partner by the Partnership for such taxable period, (ii) assuming that such Partner is subject to tax at the Assumed Tax Rate, and (iii) computed without regard to any increases to the tax basis in the Partnership pursuant to Code Sections 734(b) or 743(b). In the case of PubCo, such Assumed Tax Liability shall also be computed without regard to any other step-up in basis for which PubCo is required to make payments under the Tax Receivable Agreement. In addition, for the avoidance of doubt, any item of income, gain, loss, or credit earned (or that would be treated as earned based on an interim closing of the books) by the Partnership prior to the Closing shall be disregarded for purposes of calculating any Partner’s Assumed Tax Liability.

“Assumed Tax Rate” means the highest combined maximum marginal United States federal, state and local income tax rate ((w) taking into account the tax on net investment income under Code Section 1411 and the self-employment taxes set forth in Code Section 1401, as applicable, (x) not taking into account any deduction under Code Section 199A or any similar state or local Law, (y) taking into account the character (e.g., capital gains or losses, dividends, ordinary income, etc.) of the applicable items of income, and (z) taking into account the deductibility of state and local taxes to the extent applicable), applicable to (A) an individual residing in New York City or (B) a corporation doing business in New York City (whichever results in the application of a higher state and local income rate) during each applicable Fiscal Quarter with respect to such taxable income as determined by the General Partner in good faith.

“Tax Distribution” has the meaning set forth in Section 4.2.

“Tax Distribution Date” means, with respect to each calendar year, (a) April 10, June 10, September 10, and December 10 of such calendar year, which shall be adjusted by the General Partner as reasonably necessary to take into account changes in estimated tax payment due dates for U.S. federal income taxes under applicable Law, and (b) in the event that the General Partner determines (which determination shall be made prior to the date specified in this clause (b)) that the Tax Distributions made in respect of estimated taxes as described in clause (a) were insufficient to pay each Holder’s Assumed Tax Liability for the entirety of such year, April 10 of the following year (for purposes of making a Tax Distribution of the shortfall).

Provisions

Section 3.3 Additional Funds and Capital Contributions.

(a) General. The General Partner may, at any time and from time to time, determine that the Partnership requires additional funds (“Additional Funds”) for the acquisition or development of additional Assets, for the redemption of Partnership Units, for the payment of Tax Distributions or for such other purposes as the General Partner may determine. Additional Funds may be obtained by the Partnership, at the election of the General Partner, in any manner provided in, and in accordance with, the terms of this Section 3.3 without the approval of any Limited Partner or any other Person.

Section 4.1

Distributions Generally. Subject to Section 4.5, the General Partner may cause the Partnership to distribute all or any portion of available cash of the Partnership to the Holders of Partnership Units in accordance with their respective Percentage Interests of Partnership Units on the Partnership Record Date with respect to such distribution. Notwithstanding the foregoing, except for Tax Distributions made in accordance with Section 4.2 or if expressly provided otherwise in an Approved Management Award Agreement, distributions shall not be made with respect to any Unvested Units unless and until such time as such Unvested Units become Vested Units pursuant to the applicable Management Award Agreement.

Section 4.2

Tax Distributions. Prior to making distributions pursuant to Section 4.1, on or prior to each Tax Distribution Date, the Partnership shall be required to, subject only to (i) Section 4.5, (ii) Available Cash and (iii) the terms and conditions of any applicable Debt arrangements (and the General Partner will use commercially reasonable efforts not to enter into Debt arrangements the terms and conditions of which restrict or prohibit the making of customary tax distributions to the Partners), make pro rata distributions of cash to the Holders of Partnership Units (in accordance with their respective Percentage Interests of Partnership Units), including Class P Units and Equitized Class P Series Units (whether Vested Units or Unvested Units), in an amount sufficient to ensure that each such Holder receives a distribution at least equal to such Holder’s Assumed Tax Liability, if any, with respect to the relevant taxable period to which the distribution relates (“Tax Distributions”); provided, however, that Tax Distributions may be made disproportionately with respect to Class P Units and Equitized Class P Series Units vis-a-vis Common Units, and regardless of whether Tax Distributions are made with respect to Common Units, to the extent set forth in the proviso of the next sentence; provided, further, to the extent any Tax Distribution is made disproportionately with respect to Class P Units and Equitized Class P Series Units vis-a-vis Common Units, the portion of such Tax Distribution disproportionately made in respect of any Class P Unit or Equitized Class P Series Unit shall serve as an advance of (and shall reduce the amounts otherwise distributable or reserved in respect of) such Class P Unit or Equitized Class P Series Unit following such disproportionate Tax Distribution; and provided, further, in no event shall the Partnership be required to make any Tax Distributions on the First Tax Distribution Date and the amount of Tax Distribution required on the succeeding Tax Distribution date will be increased by such shortfall until the full amount of required Tax Distributions on the First Tax Distribution Date has been made. Notwithstanding the foregoing, distributions pursuant to this Section 4.2, if any, shall be made to the Partners only to the extent all previous distributions to the Partners pursuant to Section 4.1 with respect to the taxable period are less than the distributions the Partners otherwise would have been entitled to receive with respect to such taxable period pursuant to this Section 4.2, provided that, the per Unit amount of any distributions made pursuant to Section 4.1 that would have been allowable as Tax Distributions but for this sentence shall be made as Tax Distributions pursuant to this Section 4.2 to the holders of Class P Units and Equitized Class P Series Units to the extent such holders are not otherwise entitled to distributions pursuant to Section 4.1, as applicable, as of the applicable Tax Distribution Date. For the avoidance of doubt, if for any reason the Partnership on any Tax Distribution Date does not make the full amount of distributions required under this Section 4.2 (determined without regard to the limitations in clauses (i), (ii), and (iii) of the first sentence in this Section 4.2), the amount of Tax Distributions required on the succeeding Tax Distribution Date will be increased by such shortfall until the full amount of required Tax Distributions have been made.

Where the LPA does not provide for a tax distribution for self-employment tax and a limited partner does not pay the tax liability, the general partner may have derivative liability for the unpaid unemployment tax. This issue can arise in surprising ways especially when an employee status changes to a status of a partner in a partnership. Often, partnerships grant profits interest as an inducement for employees to enter into or remain in the service of the partnership and as additional incentive during such service. When an employee receives a profits interest, their status can change from employee to self-employed partner. The IRS takes the position that a partner cannot be an employee of a partnership. See Rev. Rul. 69-184, 1969-1 C.B. 256; see also Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(c)(2)(iv); IRS Gen. Couns. Mem. 34001 (Dec. 23, 1969); IRS Gen. Couns. Mem. 34173 (July 25, 1969); Riether v. United States, 919 F. Supp. 2d 1140 (NM 2012)(finding that LLC members’ distributive share of income was subject to self-employment tax because they were not and did not resemble limited partners).

Thus, because a partner in a partnership cannot simultaneously be treated as an employee of that same partnership for employment tax purposes, self-employment taxes may be imposed on the entire income of the employee. The advantage that the profits interest provides may be adversely affected by the application of the self-employment taxes. If the partner does not pay their self-employment taxes, the unpaid taxes become debt of the partnership under federal law. Under state law, the partners become derivatively liable for that debt. The IRS may enforce a derivative liability that arises under state partnership law against the general partner for the tax debts of a partnership. See Young v. U.S. I.R.S., Dep't. of Treasury, 387 F. Supp. 2d 143, 145 (E.D. N.Y. 2005)(held that a general partner was jointly and severally liable under New York law for the partnership’s unpaid federal employment taxes, unpaid federal income taxes, and unpaid federal unemployment taxes); see also Young v. Riddell, 283 F.2d 909, 910 (9th Cir. 1960)(providing that general partners are “personally liable for the debts and liabilities of the partnership, including its tax liability”); United States v. Papandon, 331 F.3d 52, 55 (2d Cir. 2003) (“state law determines a partner’s liability for partnership obligations”); Remington v. United States, 210 F.3d 281, 283 (5th Cir. 2000) (under state law, “the IRS is entitled to collect the trust fund tax liability, indisputably a partnership debt, from any one of the general partners,” because “[t]he partnership is the primary obligor and its partners are jointly and severally liable on its debts”); Ballard v. United States, 17 F.3d 116, 118 (5th Cir. 1994) (“it is state law that determines when a partner is liable for the obligations-including employment taxes-of his partnership”); United States v. Hays, 877 F.2d 843, 844 n.3 (10th Cir. 1989) (“the liability of a general partner for the tax obligations of the partnership is determined by state law rather than federal law”); Calvey v. United States, 448 F.2d 177, 180 (6th Cir. 1971) (same).

Looking ahead: As evidenced by pending cases, both at the Tax Court and Circuit Courts, the IRS is confident in its functional analysis theory and has applied it to multiple funds with multi-billion dollars in AUM. Passive investors should be diligent in reviewing their tax distribution provisions to assess whether the funds’ tax distributions include coverage for self-employment tax, and if so, to what extent. Additionally, given that the functional analysis test is applied to the substance of the activities in a partnership, limited partners must be cautious of activities that will pull them out of the exception for limited partners as such. In rare cases, the general partner may also want to review withholding provisions to make sure that the tax liabilities of limited partners for self-employment tax that are imposed are picked up as a loan to the limited partners or as an advance to the limited partners against future distribution or some other arrangement.

The IRS, no doubt, has been on a winning streak, but it is important to note that this issue is still unsettled in the circuit courts. If a circuit split arises, the Supreme Court may exercise its judicial discretion to grant certiorari. Until then, grab some popcorn and follow the ongoing litigations below:

Tax Court: pending cases

Point72 Asset Management LP v. Commissioner, Docket No. 12752-23.

Point72 Asset Management LP is a hedge fund operating multiple strategies (long/short equity, systematic, macro) and private market investments, with approximately $37.7 billion in AUM and more than 190 investing teams.

MKP Capital Management LP v. Commissioner, Docket No. 126-25

MKP Capital Management LP is a hedge fund using discretionary global macro strategies to generate absolute returns across market cycles, with billions in AUM.

Riverstone Equity Partners LP v. Commissioner, Docket No. 17512-24

Riverstone Equity Partners LP is a private equity firm specializing in energy-sector leveraged buyouts, growth capital, and credit investments, with billions in raised capital.

Moon Capital Management LP v. Commissioner, Docket No. 1929-25

Moon Capital Management LP is a hedge fund employing fundamental equity long/short strategies focused on global emerging/frontier markets, with millions in AUM.

U.S. Court of Appeals: pending cases

Sirius Solutions, L.L.L.P. v. Commissioner, No. 24-60240 (5th Cir.).

Denham Capital Management LP v. Commissioner, No. 25-1349 (1st Cir.).

US Court of Appeals: expected appeal

Soroban Capital Partners LP v. Commissioner, [] (2ndCir.).

No Legal Advice or Attorney-Client Relationship: The general information provided in this publication is written solely for educational purposes and shall not be construed as legal advice. In addition, the information in this publication shall not be construed as an offer to represent you, nor is it intended to create, nor shall the receipt of such information constitute, an attorney-client relationship.

Terms and Conditions: The publisher owns all legal rights, including intellectual property (registered or not), to this online newsletter/blog’s content, and any person or entity accessing it (including via automated means) agrees not to reproduce, adapt, distribute, commercially exploit, or create derivatives without the publisher’s express written consent, though they may view, print individual pages (not photocopy), and store pages locally for personal, non-commercial use.